The evolutionary relations of sunken, covered, and encrypted stomata to dry habitats in Proteaceae

by Jordan G. J., Weston P. H., Carpenter R. J., Dillon R. A., Brodribb T. J. (2008)

School of Plant Science, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart 7001, Australia

Gregory J. Jordan, Peter H. Weston, Raymond J. Carpenter, Rebecca A. Dillon, Timothy J. Brodribb

===

in Am. J. Bot. 95(5): 521-530 – https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.2007333 –

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.3732/ajb.2007333

Abstract

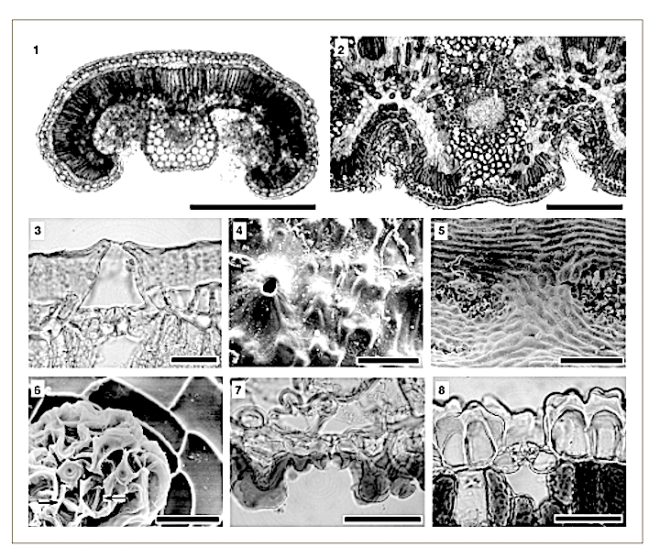

Sunken, covered, and encrypted stomata have been anecdotally linked with dry climates and reduced transpiration and therefore have been used to infer dry palaeoclimates from fossils.

This study assesses the evolutionary and ecological associations of such stomatal protection in a model system—the diverse southern hemisphere family Proteaceae. Analyses were based on the morphology of over 1400 Australian, South African, New Caledonian, New Zealand, and South American species, anatomy of over 300 of these species, and bioclimatic data from all 1109 Australian species.

Ancestral state reconstruction revealed that five or six evolutionary transitions explain over 98% of the dry climate species in the family, with a few other, minor invasions of dry climates.

Deep encryption, i.e., stomata in deep pits, in grooves, enclosed by tightly revolute margins or strongly overarched by cuticle, evolved at least 11 times in very dry environments.

Other forms of stomatal protection (sunken but not closely encrypted stomata, papillae, and layers of hairs covering the stomata) also evolved repeatedly, but had no systematic association with dry climates.

These data are evidence for a strong distinction in function, with deep encryption being an adaptation to aridity, whereas broad pits and covered stomata have more complex relations to climate.

You must be logged in to post a comment.